Farming on the Livingston Homestead in Cold Bay, Alaska

In this short article, I recall what it was like to farm on my family’s homestead in Cold Bay on the Alaska Peninsula.

The Move to Cold Bay

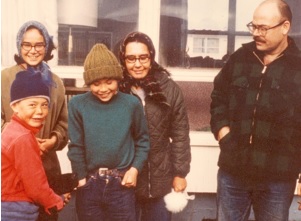

My family moved to Cold Bay on the Alaska Peninsula in 1961. My father served as a machine gunner and radio technician during World War II, and was stationed at Blinn Lake near the town of Cold Bay in the 1950s. He must have liked Cold Bay because after the Army he joined FAA (Federal Aviation Agency) as an electronics technician. We (dad, mom, sister, brother, me) arrived on the M/V Expansion (a slow moving mail boat) and moved into an FAA housing duplex right next to the 10,000 foot long runway (Livingston, 2013). See photograph below of my family standing in front of our FAA duplex.

Figure 1 My Family at FAA in Cold Bay

My Dad

My dad (Bob) was born in Kansas during the Dust Bowl era and lived in most of the western states in the US while his father pursued funding to feed a family of eight. My dad’s family was farmers including wheat in Illinois, corn in Kansas, and potatoes in Scotland. On the other hand, my mom’s family was fishermen from Alaska. My dad was a bit of an independent rebel and believed in a person’s capability to survive without help for anyone else — particularly government agencies.

The Livingston Homestead

Something motivated him to file for a homestead at the mouth of Trout Creek where it flowed into Cold Bay. The UnangaxÌ‚ name for the creek translates roughly to “Salty Creek” perhaps due to the large estuary that forms when the tide fills the mouth with ocean water. We built our own bridge, houses, steam bath, farming fields, and everything we needed to survive. We salvaged lumber and building supplies from World War II structures left abandoned. Dad even dug up Army vehicles, cleaned them up, and got them running again. He salvaged a crane and several geodesic domes that covered radars used by the military. Please see satellite view of the Livingston homestead below from OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap, 2017). I added the rectangles of the approximate location of the Lower 40 and the Upper 40, but they are not to scale (likely drawn larger than they actually were).

Figure 2 Open Street Map View of Livingston Homestead

The soil on the homestead was dark brown and rich. We rototilled two areas, one that we called The Upper Forty, but it was no 40 acres. It might have been an acre. There was another region towards the coast of the bay that we also rototilled. In both of these areas we made rows of dirt and planted potatoes. I cannot remember where Dad got the potato seeds from, maybe the Matanuksa Valley near Palmer. Every spring we got a specific amount (say 300 pounds) that we planted; and, every fall we harvested a lessor amount (maybe 50 pounds). As a kid growing up I Cold Bay, I found it difficult to understand how people made a living at farming.

Cold Bay Weather

The summers in Cold Bay are short, wet, cool (40s), and windy. The average annual temperatures in Cold Bay between 1950 and 2016 indicate a low average of 33.6 degrees and a high of 42.9 degrees (WRCC, 2017). Cold Bay was chosen as a location during World War II to build an airport due to the cloudy overcast so that Japanese pilots might not find and bomb the airport (Garfield, 1969). The sun shone rarely when we were kids growing up in Cold Bay, and — when it did — we wondered what sin we had committed to have that bright celestial body in the sky shining upon us.

Our Greenhouse

We built a greenhouse using creosoted pilings we found on the beach to build the walls. We angled these outward at an angle of maybe 45 degrees and covered them with corrugated sheet metal. The roof we made from curved metal ribbing that we salvaged from military Quonset huts. It was high-carbon steel that could not be drilled, so Dad shot holes in it with his Army issue M1 Garand 30-06 rifle. We covered the roof with translucent fiberglass that Dad purchased from Anchorage. We built raised boxes from salvaged lumber and put seaweed in the bottom of the boxes. Dad got an Onan electrical generator that he put into a small shed on one end of the greenhouse. He did not run it often, but the heat from the generator helped heat the greenhouse. We planted carrots, radishes, and tomatoes in the raised beds in the greenhouse. Outside of the greenhouse in the lee of the wind provided by the walls, we planted horseradish. I remember that it was extremely hot.

Our Family was Poor

Our family was very poor during the years that we lived on the homestead. I have not yet found the Social Security records from that time, but neither my Dad nor my Mom were working, so I imagine our entire family annual income was $0. In addition to farming, we fished for salmon, trout, and halibut. We dug clams at the head of the bay. We hunted caribou. We got fresh water from the spring below the homestead, driftwood from the beach for our 55-gallon drum stoves, and took steam baths in a steam bath we built ourselves. Even though we were poor, we did not know it.

Other Attempts at Farming in Cold Bay

I do not know of anyone else who farmed in Cold Bay. The Brown family tried raising cows and sheep in the nearby village of Akutan where – like our farming venture – theirs did not end up being lucrative (Dodd Brown, 2014). When the Russians attempted farming in the Aleutians in the 1700s and 1800s, they did not have much success (Veniaminov, 1984).

Indigenous versus Western or European Farming

Yet, for at least 8,000 years, the indigenous people of the region found all they needed to survive and thrive, including plants utilized for medicinal, spiritual, and hunting purposes (Laughlin, 1984). Perhaps the success versus non-success approach may be viewed from an indigenous point of view as opposed to a Western or European model of farming in the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula.

Return to the Livingston Homestead in 2010

When I returned to my families homestead in 2010, there were no potatoes nor horseradish growing. The indigenous plants on the other hand were doing just fine.

Figure 3 Photograph of Indigenous Plants of Cold Bay

Bibliography

Dodd Brown, J. (2014). Cow Woman of Akutan. Anchorage, Alaska: Publication Consultants, Inc.

Garfield, B. (1969). The Thousand Mile War. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Laughlin, W. S. (1984). Aleuts: Survivors of the Bering Land Bridge. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Livingston, M. (2013). Cold Bay, Alaska. Anchorage, Alaska: Blurb, Inc.

OpenStreetMap. (2017, October 29). OpenStreetMap. Retrieved from OpenStreetMap: https://www.openstreetmap.org

Veniaminov, I. (1984). Notes on the Islands of the Unalashka Distric. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska.

WRCC. (2017, October 29). Cold Bay AP, Alaska. Retrieved from Western Regional Climate Center: https://wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?ak2102

About mlivingston2

Twitter •