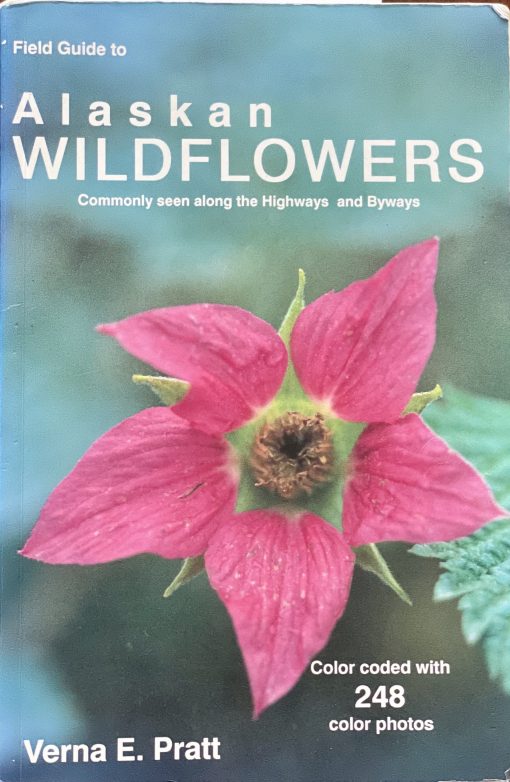

It’s been almost twenty years since I first picked up a copy of Verna Pratt’s Field Guide to Alaskan Wildflowers, A Roadside Guide. While it might be a little unnecessary or even redundant to offer a literary review of one of Alaska’s most famous Master Gardeners, her introduction, penned in 1990, is just as prescient now as it was two decades ago.

In her introduction, Verna makes it clear the book was created with the amateur botanist in mind. Given I satisfy amateur criteria, I don’t mind telling you, I think she was successful. Writing and arranging the book by color focuses on the most obvious attention-grabbing characteristic of many wildflowers. Including a printed corresponding facsimile of coded tabs on the page edges, also based on electromagnetic frequency, helps expedite locating the general page range of color groups on the fly and probably in the rain. All pages are plastic coated making it slightly water resilient, tempting to extinguish a mosquito with, and durable enough to hold up to miles in a backpack. And, though one could split hairs over whether or not the 248 included photos are better in another publication, Verna’s collection does not exclusively ignore other diagnostically important parts of flowers like stem and leaf structures. What’s more, the book is widely available in bookstores, grocery stores, and gas stations.

Appendix Appraisal

The collection of photos and intended use of identifying plants in the field is not the only aspect of Verna’s book that encourages one to “look more closely at the fine details of a plant.” In fact, the appendices of Alaskan Wildflowers are just as valuable as the rest of the work.The included short descriptions of plant family characteristics are helpful for being able to note and recognize the overarching characteristics of different groups of plants. The pictorial glossary includes close up photography and a corresponding hand drawn and labeled diagram of flower reproductive parts. Also included are drawings and labels of flower types, flower grouping structures, and, leaf arrangements, shapes, veins, and edges. All of the drawings are presented in a fashion that encapsulates the average differences of said characteristics. This helps mitigate the resulting difficulties of the fact that no individual plant located in the field will look exactly like the pictures in a field guide, along with the problem of using photography likely framed around aesthetically highlighted characteristics even less indicative of average individual plants.

The appendices also include a list of outstanding and regularly visited spots in Alaska and a concise list of the most common flowers, and the most common colors those same flowers will take on in each of the respective locations. This section is complimented by a comprehensive blooming time chart organized in a floating horizontal bar graph set against a monthly horizontal axis and vertical species list.

For the foragers, Verna includes a comprehensive and concise list of preparation methods, and specific culinary uses for many of the edible varieties featured. And fortunately, for both the more ignorant and adventurous, this section is promptly followed up with a list of poisonous plants.

The last section of the appendices, is a glossary of botanical terms not only helpful for further engaging all of the explanatory and descriptive elements of any plant guide, but for also equipping one with some level of formal botanical vocabulary to use in discussion with and intimidation of others.

Verna’s appendices are certainly a boon to the amateur botanist who would like to take their hobby a bit nerdier (which I mean in the most complimentary fashion). Yet, I emphasize this information because her appendices are also exceedingly rich in their ability to sharpen one’s focus and recognize frequently used diagnostic structures. For instance, the distinction between sitka valerian, valerian sitchensis, and capitate valerian, valerian capitata, is more easily made by noting differences in the shapes of their lower and basal leaves; and, high bush cranberry, viburnum edule, can often be distinguished from northern red currant, ribes triste, by the number of lobes on their leaves. Studying the information in the appendices of Verna’s guide can help one combine this sort of structural knowledge with field observation to generate tools for clearing up confusion between such species.

Complimenting Resources

Because of all of these rich resources, I have read Verna’s book dozens of times and use it as my primary field guide. It has been so inspirational I often defer to it when cross-referencing; which, is another fantastic habit for those who are just that into wildflowers. For the Chugach National Forest enthusiast, cross-referencing Verna’s Alaskan Wildflowers with the USDA Forest Services’ Vascular Plant Identification Guide to the Chugach National Forest provides a set of information that can not only further enrich attention to distinction in detail with a different complimentary set of descriptions, but also expand the number of species covered, and add to the comprehensiveness of the collection of common names. This last addition is especially helpful since I suspect it is safe to assume I’m not the only one whose wildflower identification suggestions regularly get challenged. Which is why, perhaps, it is worth noting a handful of common names that could be added to Verna’s collection to help clear up unnecessary disagreements.

6 Common Name Additions

I chose six species because of both their ubiquitousness and their ability to inspire argumentative stalemates in debates over nomenclature. I don’t bring these distinctions up to suggest one common name should necessarily be privileged over all others, but instead that the happy side effect of using these two resources in tandem results in an expansion of one’s awareness of multiple common names and, after bearing witness to said polite disagreements, makes for more pleasant company. I’ll begin with a common alpine ground cover.

Verna refers to cassiope stelleriana as moss heather on page 66 and cassiope tetragona as bell heather, also on page 66. The USFS refers to moss heather (cassiope stelleriana) as steller’s cassiope on page 17, a fitting companion to our steller sea lions and jays. And, the USFS refers to bell heather (cassiope tetragona) on page 18, as four-angled cassiope, highlighting the arrangement of leaves in four stacked rows.

Two species of alpine saxifrage also stand out: saxifraga bronchialis on page 39 and saxifraga punctata on page 59. The distinction in common name for saxifrage bronchialis may be splitting hairs, but Verna uses yellow spotted saxifrage while the Forest Service refers to it as yellowdot saxifrage. Just like the confusion that can result from a descriptive phrase said aloud like ‘Panda: Eats, Shoots & Leaves’, it may be the case that recognizing saxifraga bronchialis has yellow dots instead of being yellow and spotted could clear up problems with ambiguous reasoning. And while this distinction may not be helpful for anyone but me, the common name for saxifrage punctata employed by the forest service is intuitive of the shape of the basal leaves for which the plant is distinguished from other saxifrage. The USFS’ use of the name heart-leaved saxifrage, possibly in this author’s estimation alone, may be more intuitive than Verna’s use of brook saxifrage for saxifraga punctata.

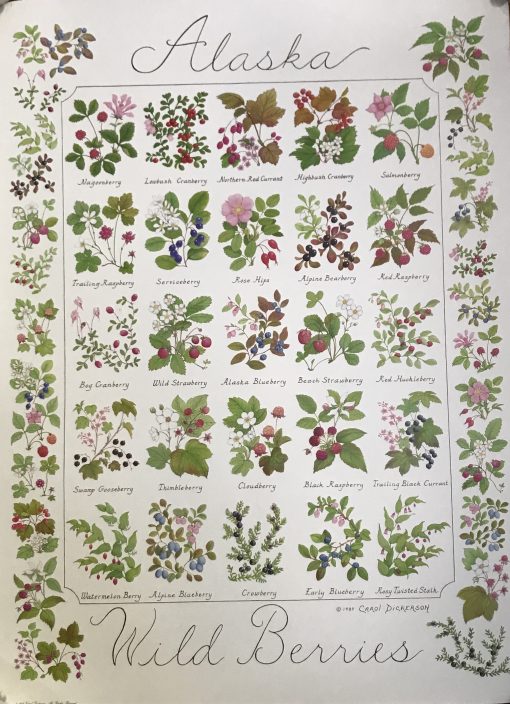

While the Forest Service wins my vote when it comes to saxifrages, I favor Verna’s use of trailing raspberry, on page 67, over the Forest Service’s naming of rubus pedatus as five-leaf bramble. This is partly because the berries bear a striking resemblance to small raspberries and partly because less folks know what a bramble is. Additionally, Carol Dickerson, in her exceedingly popular botanical poster Alaska Wild Berries also calls rubus pedatus trailing raspberry. So, while there is no real way to parse out which of the names is more appropriate, the sheer popularity of Dickerson and Verna’s publications measured with the authoritativeness of the Forest Service’s work helps illustrate that being aware of both names will be helpful for natural history bilingualism.

One last alpine plant with more than one popular alias worth keeping in mind is leutkea pectinata. While Verna refers to leutkea pectinata as Alaska spirea, the Forest Service’s use of the name leutkea is just as in vogue.

Good Luck!

Hopefully this information was a little helpful for alleviating the all-too-common situation when folks argue over equally accepted common names. Hopefully it was even more helpful in encouraging careful observation of Alaska’s wild flowers. I would like to whole heartedly recommend the activity, and suggest that anyone is capable of contributing to the great body of botanical research, and thereby enriching the human corpus of knowledge, if they are willing to look closely at the details of a plant.

About Hugh Deery III

Twitter •